VIEW OSAKAシリーズ #5「REMNANTS1926-1989 昭和残存」を

平成最後の「昭和の日」に出版しています。

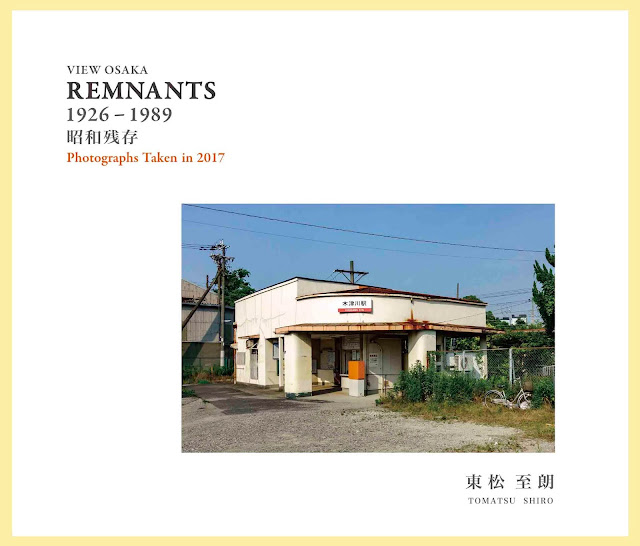

表紙

中表紙

奥付

VIEW

OSAKA 「REMNANTS

1926-1989 昭和残存」<昭和残存:Showa

Zanzon>

Photographer

: Tomatsu, Shiro

Design:Yabumoto,

kinumi Noda,

Hiromi

Printing

Director : Hirata、

Koji

(LIVE ART BOOKS)

Sales

and Advertising:TOMATO

FOTO HOUSES E-Mail:tomat8kv@gmail.com

Published

in April. 2019 by Siracusa Amano,

Kenichi E-Mail:siracusa@kenichiamano.com

Printed

by

Daishinsha

Printing

Co.,Ltd. in

Japan/LIVE

ART BOOKS

Collaboration

Matsuoka,

Kumiko

Tanimura

Hilgeman,

Hiromi

Paul

Hilgeman

Tokunaga.

Yoshie

Tokunaga

Institute of Photo & Art

Nankai

Electric Railway Co.,Ltd.

ISBN 978-4-9906907-4-8 定価/Price ¥3000+税(Tax)

本書はAmazon、楽天などのネット通販等で取り扱っていません

本書の問い合わせはtomat8kv@gmail.com (内藤/Naito)までお願いします。

*****************************************************************

Foreword

The

left bank district in the middle reaches of the Kizu river in Osaka

city was, until the end of the Meiji period, open farmland with a few

villages. Between Meiji 43-44, the city undertook redevelopment1

of extensive farmland north of the then Kotsuma village (covering

Tamade, Senbon and Kishinosato) dividing it into a neat grid pattern,

with the intention of creating a residential area which would connect

to the developing Osaka city center.

From

the Taisho period into the Showa, a diverse range of factories such

as spinning, textile, shipbuilding, steel, iron and mechanical

instrument manufacturing, as well as chemical and power plants were

clustering around the mid to lower reaches of the Kizu. Rentable

homes for the factory workers were built largely on the redeveloped

farmland and conversion of agricultural land to residential land

continued to take place. Shops catering for the workers also opened

and thrived.

At

the time of the Pacific War, central Osaka and factories along the

banks of the Kizu were heavily bombed by the US Air Force and

suffered great damage. The residential areas, however, escaped the

air raids. Soon after the war, the damaged factories were rebuilt,

and as the economy started to grow so did factory output. The

necessity for more housing for additional workers resulted in the

so-called “bunka jutaku” (cultural housing) being built, which

were two-storied, tiled-roofed wooden housing complexes, filling

every available space in the residential district creating a dense,

urban landscape.

From

the Showa into the Heisei during the “real estate bubble”, this

residential district being away from the Osaka center escaped the

extremely aggressive city redevelopment, and as a result much of the

Taisho-Showa period wooden housing remained. After the “bubble”

burst, as the recession took hold and factories closed down one after

another, the working families with children who had once occupied the

housing moved out. Now, the area is home to old people and

pensioners, still strongly retaining the atmosphere of the bygone

Showa era.

With

the intention of promoting a better housing environment and fire

safety, the “Osaka City Project Supporting (Demolition and)

Rebuilding of Dilapidated Private Sector Housing” was set up in

April 2011 including the “Program for Promoting the Removal of

Dilapidated Residential Buildings Along Narrow Roads” 2

which was identified as a priority. The city has since been actively

encouraging the dismantling and clearing out of the decrepit wooden

housing. Much of the cleared land still lies empty, surrounded by

metal fences.

The

left bank district in the middle reaches of the Kizu, its changes

from the Taisho to the Showa and then into the Heisei, and the

remnants of the Showa era such as the dilapidated wooden housing

complexes bring back long forgotten, nostalgic emotional peaks and

troughs felt by the Showa dwellers in downtown Osaka. But once such

housing complexes are finally taken down, as time moves on, the

cherished memories must disappear too, fading into oblivion.

Tomatsu

Shiro

<Photographs

taken between January and December 2017>

Translator’s

notes

- Direct translation for “Nōchi Kukaku Seiri Kōji” is “Agricultural Land Readjustment Construction Work”.

- The project and program were called in Japanese: “Ōsaka-shi Minkan Rōkyū Jūtaku Tatekae Shien Jigyō” and “Kyōai Dōro Endō Rōkyū Jūtaku Jokyaku Sokushin Seido” respectively.

References

- Kawabata, Naomasa and Nishinari-ku Osaka city, ed., Nishinari-ku Shi [A History of Nishinari-ku], 1968

- Furuya, Hideki, Sōseiki no Tochi Kukaku Seiri Jigyō ni Kansuru Ichi Kōsatsu: Osaka・Imamiya Kōchi Seiri Jigyō o Nentō to shite [Study on Land Readjustment Project in the Early Period: with Arable Land Consolidation Project in Imamiya village (Osaka) in mind], Kankōgaku Kenkyū Vol.12, 3/2013

Notes

on dates

Meiji

period : 1868 – 1912 /

Taisho

period : 1912 – 1926 /

Showa

period : 1926 – 1989

Heisei

period : 1989 - 2019

まえがき

大阪市の木津川中流左岸地域は明治末期まで田畑が広がる農村でした。明治43年から44年にかけ、大阪市は発展する市街中心部に繋がる住宅地への転用を目論んで、旧勝間村(玉出・千本・岸里)北部の広域な田畑を碁盤の目のように農地区画整理工事を行っています。

大正から昭和になると、木津川中下流域は紡績、織物、造船、製鉄、鉄工、化学そして機械器具など多種多様な工場が集積し、ここで働く勤労者の賃貸住宅などが区画整理地に多く建てられ、農地が宅地になって行きました。併せて勤労者世帯相手の商店も出店し大いに賑わいました。

太平洋戦争時、大阪市中心部や木津川沿岸の工場はアメリカ軍による大空襲を受け大きな被害がありましたが、この住宅地域は空襲に遭わずに済みました。戦後直ぐ、木津川沿いの工場が復興され、更に経済の発展で工場が活況となり、増大する勤労者向け住宅の需要を補うべく通称「文化住宅」という木造二階建瓦屋根の集合住宅が僅かな隙間を埋めるがごとく建てられて行きました。そして木造住宅密集地となって行きました。

昭和から平成にかけての不動産バブル期、大阪市中心部から離れたこの住宅地は、猖獗さを極めた都市再開発にさほど縁が無く、大正から昭和に建てられた多くの木造住宅が残されました。バブル後、長引く国内経済停滞による相次ぐ工場の撤退に合わせ、勤労世帯である子育て世代も転出し、今では昭和の面影を色濃く残した高齢者の街となっています。

大阪市は密集木造住宅市街地を、居住環境の改善及び防災性の向上を図ることを目的に「大阪市民間老朽住宅建替支援事業 狭あい道路沿道老朽住宅除却促進制度」(平成23年4月1日施行)を設け、積極的にこの地区の老朽木造住宅の解体撤去を支援しています。除却された跡地の多くは金網フェンスに囲まれ更地となりました。

木津川中流左岸地域の大正から昭和そして平成と、時代を経た老朽木造集合住宅などの「昭和の残渣」は、昭和を大阪の下町で生活した人達の忘れていた、そして戻ることが出来ないあの時代の喜怒哀楽の思いを呼び戻してくれます。しかし、この老朽木造集合住宅などが取り壊された後は、何時しか過ぎ去る時の流れと伴に、切ない記憶は忘却の彼方へ溶暗して行くのでしょう。

東松至朗

*西暦と元号 明治:1868年~1912年/大正:1912年~1926年/昭和:1926年~1989年/平成:1989年~2019年

参 照 1.西成区史

川端 直正 (著) 大阪市西成区 (編集) 1968年

2.創生期の土地区画整理事業に関する一考察:

大阪・今宮耕地整理事業を念頭として 古屋秀樹(著)

観光学研究 Vol.12,

2013年3月

**********************************************************

Tomatsu

san,

Thank

you very much for sending me a copy of your photographic book,

“Houses”. Sincere apologies for not sending you an email to thank

you even though I received it at the beginning of July.

I

had a lot to think about this book. The reason I couldn’t put pen

to paper for a while was because I was allowing my thoughts to

ferment in my head.

I seem to remember

writing about this before, but I was born in Shinkai Street in

Nishinari District in the living quarters of my grandfather’s

naphthalene and dye making factory. Soon after, we moved downtown to

an area called Hayashi-ji Shinka Town in Ikuno District and lived

there until I was eight years old and in my 2nd year of

primary school. We then moved again to the Nishi Tenkajaya shopping

district in Shioji Street in Nishinari District where my mother ran a

pharmacy. I was there, as the first born son, until I was 19.

Your

first book, “The Dome”, and the second, “Rivers”, both

brought back the landscape of my childhood in Osaka, as well as a

feeling of nostalgia and a sense of something irrevocably lost.

Your

third book, “Houses”, on the other hand, had a more profound

impact on me. No one living in Osaka was included in the photographs,

but only the traces of their presence; that provided a quiet impetus

giving me a feeling of déjà vu,

and I was back there, in that familiar atmosphere.

Those

houses that were built squashed together with no space in between -

people who were frugal and hard up lived there, like most of my

friends. In a long, terraced row of workmen’s houses where all the

internal layouts were exactly the same, each family lived in a tight

squeeze.

Roads

were narrow and often unpaved, with equally long and narrow shopping

streets; you could sense a brimming over of raw emotions as a result

of the stifling cheek by jowl existence. It was chaos, of a very

Asian kind.

In

essence, I don’t think there was enough space for living, for

studying or for playing.

From

time to time, I had to run away from home. To places that were

relatively rural like Sumiyoshi-shrine and Yamato river, to Sugimoto

Town where Osaka City University was, escaping, on foot.

Your

pictures, Tomatsu san, made me wonder deeply about what I wanted to

escape from. None of my friends live in those houses anymore either.

I

now work in the pharmacy department of an emergency hospital in

Hakata*

with around 250 beds.

There are seven

pharmacists with one administrator in a room of about 50m2.

A very small space indeed.

However,

when it comes to social interaction, there’s hardly any . They keep

their distance from one another as they work. After I started working

there I realised that in small to medium sized hospitals such as this

one, people come and go all the time and doctors, nurses, technicians

and administrators also change over so frequently that you never

quite feel settled.

Also,

the hospital space is the smallest size possible and there doesn’t

seem to be much money available. Hakata is, if anything, known for

its warm hearted people and I think that’s true, but in a

particular set up such as a hospital, to be too familiar may be

frowned upon. That’s human wisdom for you. You live and learn.

However, I am an oddity here, being an Osakan. I feel something is

missing, and then the “Osaka-ness” from the Showa era that in

many circumstances I was running away from pops up unexpectedly. As

Boy so the Man. It’s in my bones. I ran away yet sometimes I long

for it. Strange, isn’t it.

Tomatsu-san,

thank you for producing the “View Osaka” trilogy. When we’re

stirred by something, it makes us think. It was a good stimulus. What

are your themes going to be in the future, I wonder? I am looking

forward to finding out.

We

are both senior citizens now . Do look after yourself.

Yours,

Yoshioka

Takashi

July

29, 2015

*Hakata

is in Fukuoka prefecture in the northern part of Kyushu.

©Tomatsu Shiro

**********************************************************

写真集:「VIEW

OSAKA REMNANTS1928-1989 昭和残存」 解題

今までのVIEW

OSAKAシリーズは、書名を「THE DOME」、「RIVERS」、「HOUSES」、「Osaka1-chome 1-banchi/大阪一丁目1番地」でした。今回も簡単な英語かローマ字書名を考えていました。

本書は「友人からの手紙」が切っ掛けででした。2017年の一年間、大阪市西成区内の国道26号線と木津川に囲まれた範囲にある昭和の名残を主体に写真撮影しています。そして、書名は「SHOWA」を考えました。

ほぼ写真集原稿が出来た頃、来日していた欧州の知人に、「このような写真集を計画している。多くの欧米の人にも視てもらいたいと思ってる」と話し、原稿案を差し出すと、いきなり内容も視ずに書名の「SHOWA」を指さし、語気強く「NO! NO!!

・・・・!」と口にしました。つたない英語力の私は、恐らく「欧米の人にも見てほしいなら、このタイトルは止めろ」ということだなと何となく理解したつもりでした。

後日、大学を昭和40年代に卒業しすぐに渡欧され、現在も欧州で仕事をされている日本人女性に下記のようなメールを送り尋ねました。

写真集の書名で「SHOWA」を使わないほうが良いと助言頂きました。今一度私の理解が良く出来ていません。ヨーロッパでは「SHOWA」の綴りが不適切な理由を教えていただきたのですが、差し支えない範囲でお教えください。

そして、届いた回答は・・・

東松さま、SHOWA(しょーわ)ですが、第2次世界大戦時にドイツのナチによって行われた大量虐殺は、ホロコーストあるいは ショーア(Shoah,

Shoa、Sjoa)とも呼ばれているそうです。

日本ではショーアの方は知られていませんが多分ヘブライ語ではないかと思います。ヘブライ語はユダヤ人以外には遣われない言葉です。

ショーア

はユダヤ系の人、ドイツ人にとっては、聴き捨てならない言葉ですし、他のヨーロッパ人にとっても嫌な記憶につながります。Wが入っていて違うと言われるかもしれませんが、日本語での「ワ」と「ア」の歴然とした違いとちがい、向こうの発音では、owa は oah,

oa, にもっと近いです。

特に速く言うと。 また、ヘブライ語を知らない人たちにとってshowa という綴りもあるのかなと思われる可能性も十分あります。まぎらわしいです。書名だけ見たら、ホロコーストの本だと間違われたり、内容を見ても、何故これがホロコーストなんだろうと思われたりする可能性があるわけです。

分かっていただけますか。

この助言により書名には「SHOWA」を使わないことにしました。

本書は平成29年(2017年)に、大阪市西成区内の国道26号線と木津川に囲まれた範囲で見ることができる昭和の「面影、遺構、残存物等」が対象です。そこで、「SHOWA」の代わりに昭和の年代を意味する西暦1928年~1989年と、「面影、遺構、残存」を意味する英語の複数形REMNANTSを選び、「REMNANTS 1928-1989」とすることにしました。

ただ、英文書名「REMNANTS 1928-1989」だけでは日本で充分理解してもらえないと思い、和文書名「昭和残存」を付記する形にしました。

本書は、平成最後の「昭和の日」(2019年4月29日)に出版しています。

****************************************************************